Working with time¶

Overview¶

With real-time data, nothing is more important to understand than the impact of time, including time zones and Daylight Savings Time (DST).

This page explains the different functions for working with time in Tinybird when using, storing, filtering, and querying data. It also explains functions that may behave in ways you don't expect when coming in from other databases, and includes with example queries and some test data to play with.

Read Tinybird's "10 Commandments for Working With Time" blog post to understand best practices and top tips for working with time.

Resources¶

If you want to follow along, you can find all the sample queries & data in the timezone_analytics_guide repo.

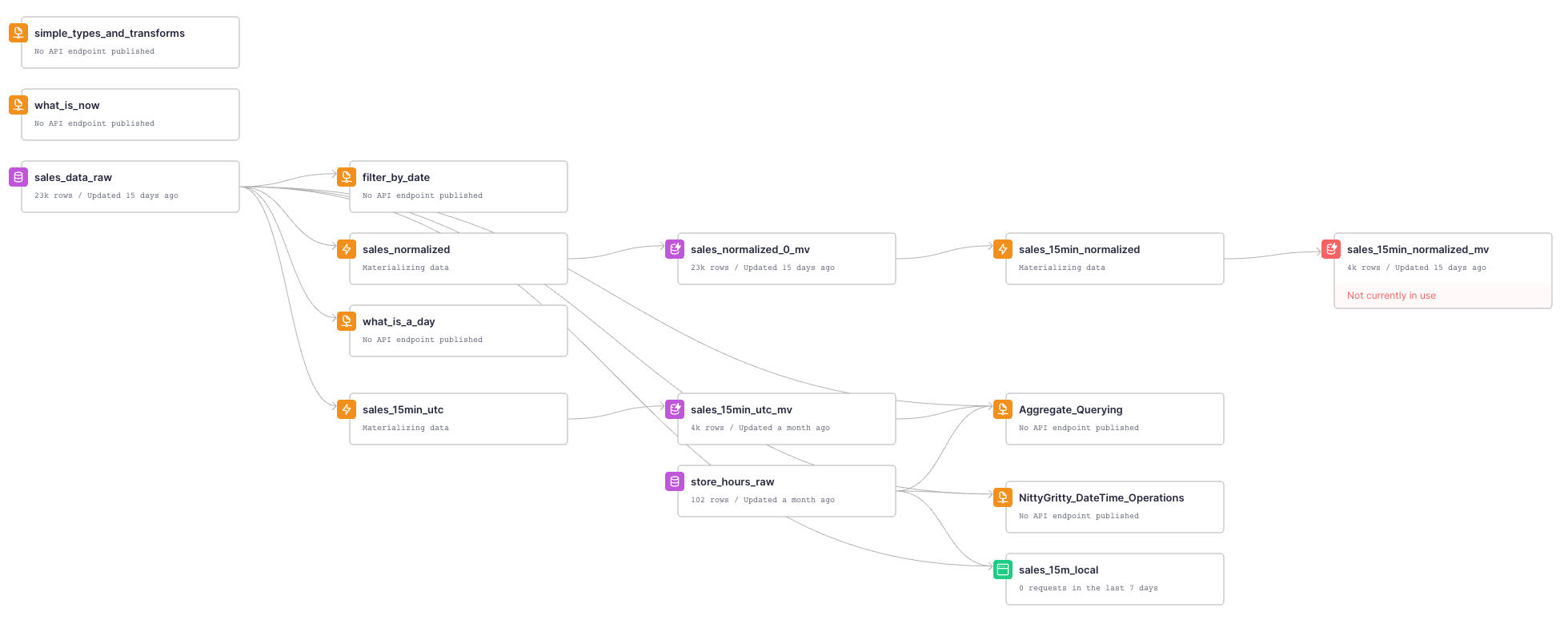

The repo contains several examples that this page walks through:

Time-related types in Tinybird¶

In the companion Workspace, this section is in the Pipe simple_types_and_transforms.

There are basically two main Types, with several sub-types, when dealing with time in Tinybird - the first for dates, and the second for specific time instants.

For dates, you can choose one type or another depending on the range of dates you need to store.

For time instants, it will depend not only on the range, but also on the precision. The default records seconds, and you can also work with micro or nanoseconds.

Date and time types

| Type | Range of values | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Date | [1970-01-01, 2149-06-06] | |

| Date32 | [1900-01-01, 2299-12-31] | |

| DateTime | [1970-01-01 00:00:00, 2106-02-07 06:28:15] | Time zone: More about that later. |

| DateTime64 | [1900-01-01 00:00:00, 2299-12-31 23:59:59.99999999] | Precision: [0-9]. Usually: 3(milliseconds), 6(microseconds), 9(nanoseconds). Time zone: More about that later. |

Note that this standard of appending -32 or -64 carries through to most other functions dealing with Date and DateTime, as you'll soon see.

Transform your data into these types¶

Date from a String¶

Various ways of transforming a String into a Date:

SELECT '2023-04-05' AS date, toDate(date), toDate32(date), DATE(date), CAST(date, 'Date')

| time | toDate(time) | toDate32(time) | DATE(time) | CAST(time, 'Date') |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-04-05 | 2023-04-05 | 2023-04-05 | 2023-04-05 | 2023-04-05 |

Store a date before 1970¶

You can use the toDate32 function, which has a range of [1900-01-01, 2299-12-31]. If you try to use the normal toDate function, you'll get the boundary of the available range - this might trip up users coming from other databases who would expect to get an Error.

select toDate('1903-04-15'), toDate32('1903-04-16')

| toDate('1903-04-15') | toDate32('1903-04-16') |

|---|---|

| 1970-01-01 | 1903-04-16 |

Parse other formats into DateTime¶

You can use the parseDateTimeBestEffortOrNull function to parse a string into a DateTime, and if it fails for some reason, it will return a NULL value. This is your best default option, and there are several others which give different outcome behaviors, like parseDateTimeBestEffort (gives an error on a bad input), or parseDateTimeBestEffortOrZero (returns 0 on bad input).

Also remember to use the -32 or -64 suffixes for the functions that return a DateTime, depending on the range of dates you need to store.

Tinybird's Data Engineers know these to generally work with typical output strings experienced in the wild, such as those produced by most JavaScript libraries, Python logging, the default formats produced by AWS and GCP, and many others. But they can't be guaranteed to work, so test your data! And if something doesn't work as expected, contact Tinybird at support@tinybird.co or in the Community Slack.

How soon is Now()?¶

In the companion Workspace, this section is in a Pipe called what_is_now.

The function now gives a seconds-accuracy current timestamp. You can use the now64 function to get precision down to nanoseconds if necessary.

They will default to the time zone of the server, which is UTC in Tinybird. You can use the toDateTime function to convert to a different time zone, or toDate to convert to a date.

Be mindful of using toDate and ensuring you are picking the calendar day relative to the time zone you are thinking about, otherwise you will end up with the UTC day instead by default. You might want to use the convenience functions today and yesterday instead.

SELECT now(), toDate(now()), toDateTime(now()), toDateTime64(now(),3), now64(), toDateTime64(now64(),3), toUnixTimestamp64Milli(toDateTime64(now64(),3)), today(), yesterday()

| now() | toDate(now()) | toDateTime(now()) | toDateTime64(now(),3) | now64() | toDateTime64(now64(),3) | toUnixTimestamp64Milli(toDateTime64(now64(),3)) | today() | yesterday() |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021-03-19 19:15:00 | 2021-03-19 | 2021-03-19 19:15:00 | 2021-03-19 19:15:00.000 | 2021-03-19 19:15:00.478 | 2021-03-19 19:15:00.478 | 1616181300 | 2021-03-19 | 2021-03-18 |

Filter by date in Tinybird¶

In the companion Workspace, this section is in a Pipe called filter_by_date.

To filter by date in Tinybird, you need to make sure that you are comparing dates of the same type on both sides of the condition.

In the example Workspace, the timestamps are stored in a column named timestamp_utc:

2023-03-19 19:15:00 2023-03-19 19:17:23 2023-03-20 00:02:59

It is extremely common that you want to filter your data by a given day. It is quite simple, but there are a few gotchas to be aware of. Let's examine them step by step.

The first thing you could imagine is that Tinybird is clever enough to understand what you want to do if you pass a String containing a date. As you can see, this query:

SELECT

timestamp_utc

FROM sales_data_raw

WHERE timestamp_utc = '2023-03-19'

Produces no results. This actually makes sense when you realize you're comparing different types, a DateTime and a String.

What if you force your parameter to be a proper date? You can easily do it:

SELECT

timestamp_utc

FROM sales_data_raw

WHERE timestamp_utc = toDate('2023-03-19')

Nope. You may realize that you are comparing a Date and a DateTime.

Ok, so what if you convert the Date into a DateTime?

SELECT

timestamp_utc

FROM sales_data_raw

WHERE timestamp_utc = toDateTime('2023-03-19')

No results. This is because the DateTime produced has a time component of midnight, which is still just a single moment in time, not a range of time - which is exactly what a Date is - all the moments between the midnights on a given calendar day.

So what you really have to do is make sure you're comparing the same kind of dates in both sides. But it will be instructive to see the results of all the transformations so far:

SELECT

timestamp_utc,

toDate(timestamp_utc),

toDate('2023-03-19'),

toDateTime('2023-03-19')

FROM sales_data_raw

WHERE toDate(timestamp_utc) = toDate('2023-03-19')

You can see that:

| timestamp_utc | toDate(timestamp_utc) | toDate('2023-03-19') | toDateTime('2023-03-19') |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023-03-19 19:15:00 | 2023-03-19 | 2023-03-19 | 2023-03-19 00:00:00 |

In order to select the day you want, you need to convert both sides of the condition to Date. In this example, you do it in the WHERE clause.

Remember that, if filtering by date, you must have a date in both sides of the condition.

Example of a good timestamp schema in Tinybird¶

Here's a few tips for the Types to use when storing timestamps in Tinybird:

- It's a good idea to include the expected time zone, or any modifications like normalization, in the

timestampcolumn name. This will help you avoid confusion when you're working with data from different time zones, particularly when joining multiple data sources. - Your time zone names are low cardinality strings, so you can use the

LowCardinality(String)modifier to save space. Same goes for the offset, which is anInt32. - You can use the

Stringtype to store the local timestamp in a format that is easy to parse, but isn't going to be eagerly converted by Tinybird unexpectedly. The length of the string can vary by the precision you need, but it's a good idea to keep it consistent across all your Data Sources. There is also theFixedStringtype, which is a fixed length string, but while it's more efficient to process it's also not universally supported by all Tinybird drivers, soStringis a better default.

Here's an example:

timestamp_utc [DateTime('UTC')], timezone [lowCardinalityString], offset [Int32], timestamp_local [String], <other data>

The details of Tinybird DateTime functions¶

In the companion Workspace, this section is in a Pipe called NittyGritty_DateTime_Operations.

This uses more of the test data, specifically the recording of metadata about Store Hours in Tokyo, to see what happens with the various functions you would expect to use, and what the outcomes are.

Things that work as expected¶

SELECT -- these are simple timezone, store_open_time_utc, store_open_time_local, -- This next one will be converted to the Tinybird server's default time zone parseDateTimeBestEffort(store_open_time_local) as parse_naive, -- This will be in the specified time zone, but it must be a Constant - you can't look it up! parseDateTimeBestEffort(store_open_time_local, 'Asia/Tokyo') as parse_tz_lookup, -- this next one stringify's the DateTime so you can pick it in UTC without TZ conversion parseDateTimeBestEffort(substring(store_open_time_local, 1, 19)) as parse_notz, -- These next ones work, but you must get the offsets right for each DST change! store_open_time_utc + store_open_timezone_offset as w_plus, date_add(SECOND, store_open_timezone_offset, store_open_time_utc) as w_date_add, addSeconds(store_open_time_utc, store_open_timezone_offset) as w_add_seconds, --- This gives you nice UTC formatting as you'd expect formatDateTime(store_open_time_utc, '%FT%TZ'), -- Because BestEffort will convert your string to UTC, you're going to get UTC displayed again here formatDateTime(parseDateTimeBestEffort(store_open_time_local), '%FT%T') FROM store_hours_raw where store = 'Tokyo' Limit 1

| timezone | store_open_time_utc | store_open_time_local | parse_naive | parse_tz_lookup | w_plus | w_date_add | w_add_seconds | formatDateTime(store_open_time_utc, '%FT%TZ') | formatDateTime(parseDateTimeBestEffort(store_open_time_local), '%FT%T') |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia/Tokyo | 2023-03-20 00:00:00 | 2023-03-20T09:00:00+09:00 | 2023-03-20 00:00:00 | 2023-03-20 09:00:00 | 2023-03-20 09:00:00 | 2023-03-20 09:00:00 | 2023-03-20 09:00:00 | 2023-03-20T00:00:00Z | 2023-03-20T00:00:00 |

Things that might surprise you¶

Here you have a column with a time in UTC, and another column with the local time zone. Tinybird has an opinion that a DateTime column must always be one specific time zone.

It also has the opinion that you must always supply the time zone as a String, and can't lookup from another column on a per-row basis.

SELECT

-- toString(store_open_time_utc, timezone) as w_tostr_lookup, << This causes an error

-- toDateTime(store_open_time_utc, timezone), << This also causes an error

toString(store_open_time_utc, 'Asia/Tokyo') as w_tostr_const, -- This is correct.

toTimezone(store_open_time_utc, timezone) as w_totz_lookup, -- This silently gives the wrong answer due to the bug!

toDateTime(store_open_time_utc, 'Asia/Tokyo') as todt_const, -- This is the best method

toTimezone(store_open_time_utc, 'Asia/Tokyo') as w_totz_const, -- this works, but toTimezone can fail if misused, so better to use toDateTime

-- Because BestEffort will convert your string to UTC, you might think you'll get the local time

-- But as the Tinybird column is UTC, that is what you're going to get

formatDateTime(parseDateTimeBestEffort(store_open_time_local), '%FT%T'),

-- formatDateTime(store_open_time_utc, '%FT%T%z')

toDate32('1903-04-15'), -- This gives the expected date

toDate('1903-04-15') -- This silently hits the date boundary at 1970-01-01, so be careful

Understand time zone handling¶

DateTimes always have a time zone. Here are the key points to note:

- A DateTime is stored as a Unix timestamp that represents the number of seconds in UTC since 1970-01-01.

- Tinybird stores a single time zone associated with a column and uses it to handle transformations during representation/export or other calculations.

- Tinybird enforces the single time zone per column rule in the behavior of native functions it provides for manipulating DateTime data.

- Tinybird assumes that any time zone offset or DST change is a multiple of 15 minutes. This is true for most modern time zones, but not for various historical corner cases.

Let's explore some areas to be aware of.

How a time zone is selected for the Column¶

Here are some general rules to observe when selecting a time zone for a column:

- If no time zone is specified, the column will represent the data in the Tinybird server's time zone, which is UTC in Tinybird.

- If a time zone is specified as a string, the column will represent the data as that time zone.

- If multiple time zones are in a query that produces a column without already creating the column with a time zone, the first time zone in the query wins (e.g. a CASE statement to pick different time zones).

- If the time zone isn't represented as a constant (e.g. by lookup to another column or table), you should get an error message.

DateTime Operations without time zone conversion¶

Tinybird provides some native operations that work with DateTime without handling time zone conversion. Mostly these are for adding or subtracting some unit of time. These operations behave exactly as you would expect.

Remember: You, as the programmer, are responsible for correctly selecting the amount to add or subtract for a given timestamp. Many incorrect datasets are produced here by incorrect chaining of time zone translations or handling DST incorrectly.

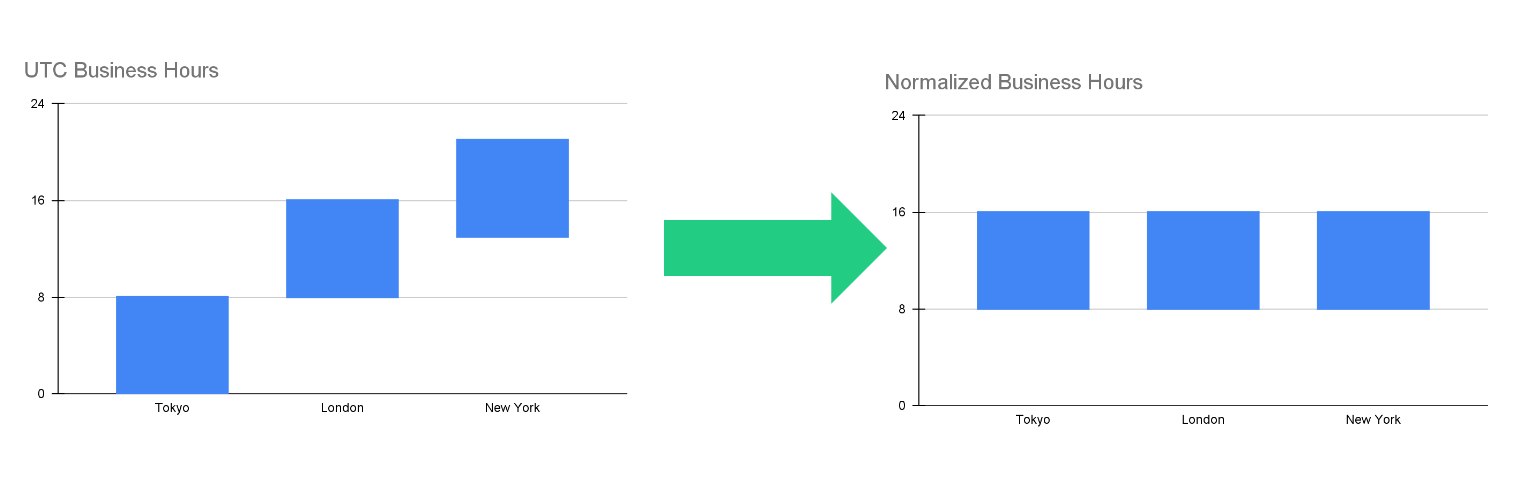

How to Normalize your Data in Tinybird¶

In the companion Workspace, this section is in a Pipe called sales_normalized.

The process of converting timestamps on the data so that they are all in the same time zone is called "time zone normalization" or "time zone conversion". This is a common practice in data analytics to ensure that data from multiple sources, which may be in different time zones, can be accurately compared and analyzed. By converting all timestamps to a common time zone, it's possible to compare data points from different sources and derive meaningful insights from the data.

Consider a sample dataset containing sales data from multiple stores which are each in different time zones. Each store is open from 0900 to 1700 local time, and you're going to shift them all to UTC:

The simplest way to do this in Tinybird is to chain standard conversion functions - first, convert from your canonical stored UTC timestamp to the store-local time zone, then extract a String representation of that local time, then convert that back into a DateTime object. Tinybird will by default present this in the server time zone, so you have to know that this dataset has been normalized and name it appropriately.

In this example you are using a CASE statement to handle each store, and the result is presented as a Materialized View in Tinybird. This has the benefit of pre-calculating the time zone shifts, you could also pre-aggregate to some time interval like 5 or 15 mins, resulting in a highly efficient dataset for further analysis. In your schema you have a String identifying the store, an Int32 for the sale_amount, and a DateTime in UTC for timestamp_utc of the transaction:

SELECT store, sale_amount,

CASE

WHEN store = 'New York' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc, 'America/New_York')))

WHEN store = 'Tokyo' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc, 'Asia/Tokyo')))

WHEN store = 'London' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc,'Europe/London')))

WHEN store = 'Madrid' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc, 'Europe/Madrid')))

WHEN store = 'Auckland' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc, 'Pacific/Auckland')))

WHEN store = 'Chatham' THEN toDateTime(toString(toTimezone(timestamp_utc, 'Pacific/Chatham')))

else toDateTime('1970-01-01 00:00:00')

END AS timestamp_normalized

FROM sales_data_raw

Note that the time zones used are all input as Strings, as Tinybird requires this. You use an else statement so that Tinybird doesn't mark the timestamp_normalized column as Nullable, which drastically impacts performance.

Good time zone test data¶

Our users do all sorts of things with their data. Issues with time-based aggregations, particularly when time zone conversions are involved, are one of the most common gotchas.

The Tinybird Data Engineers amalgamated the these into a test data set, which is comprised of:

- A facts table listing generated transactions for a set of retail stores across the world.

- Some additional columns to aid in checking processing correctness.

- A dimension table giving details about the store hours and time zones, again with additional information for correctness checking.

In the companion Workspace, these are the sales_data_raw and store_hours_raw tables respectively. The dataset is generated by this Notebook in the repo, and pregenerated fixtures from it are also in the repo.

The tricky use case¶

There is also one extra store in what is deliberately the most complex case.

Let's say you have a store in the Chatham Islands (New Zealand), which typically has a +1345hr time zone. This store records the start of the new business day at 0900 each day instead of 0000 (midnight) due to some 'local regulations'. Let's also say that this store remains open 24hrs a day, and you are recording sales through a DST change.

The Chatham Islands DST changes back one hour at 0345 local time on April 2nd, so the April 2nd calendar day will have 25hrs elapsed, however due to the store business day changeover at 0900, this will actually occur during the April 1st store business day (open at 0900 Apr1, close at 0859 Apr2).

Confusing? Yes, exactly.

In order to more easily observe this behavior, our test data records a fixed price transaction at a fixed interval of every 144 seconds throughout the business day, so your tests can have patterns to observe. Why 144 seconds is a useful number here is left as an exercise for the reader.

Why this is a good test scenario¶

- When viewed in UTC, the DST change is at 2015hrs on April 1st, and the day has 25hrs elapsed, which may confuse an inexperienced developer.

- You also have a requirement that the business day windowing doesn't map to the calendar day (the 'local regulations' above), which mimics a typical unusual requirement in business analysis.

- You can also see that the offset changes from +1345 to +1245 between Apr1 and Apr2 - this is what trips up naive addSeconds time zone conversions twice a year, as they would only be correct for part of the day if not carefully bounded.

- In addition to this, the Chatham Islands time zone has a delightful offset in seconds which looks a lot like a typo when it changes from 49500 to 45900.

- It is also a place where almost nobody has a store as the local population is only 800 people, so great for something that can be filtered from real data.

This is what makes it an excellent time zone for test data.

Test data schema¶

Take a look at the Schema, and why the various fields are useful. Note that you have used simple Types here to make it easier to understand, but you could also use the FixedString and other more complex types were described earlier in the use cases.

Store Hours:

`store` String `json:$.store` , `store_close_time_local` String `json:$.store_close_time_local` , `store_close_time_utc` DateTime `json:$.store_close_time_utc` , `store_close_timezone_offset` Int32 `json:$.store_close_timezone_offset` , `store_date` Date `json:$.store_date` , `store_open_seconds_elapsed` Int32 `json:$.store_open_seconds_elapsed` , `store_open_time_local` String `json:$.store_open_time_local` , `store_open_time_utc` DateTime `json:$.store_open_time_utc` , `store_open_timezone_offset` Int32 `json:$.store_open_timezone_offset` , `timezone` String `json:$.timezone` ,

Sales Data:

`store` String `json:$.store` , `sale_amount` Int32 `json:$.sale_amount` , `timestamp_local` String `json:$.timestamp_local` , `timestamp_utc` DateTime `json:$.timestamp_utc` , `timestamp_offset` Int32 `json:$.timestamp_offset`

Schema notes¶

The tables are joined on the store column, in this case a String for readability but likely to be a more efficient LowCardinalityString or an Int32 in a real use case.

Local times are stored as Strings so that the underlying database is never tempted to change them to some other time representation. Having a static value to check your computations against is very useful in test data.

In the Sales Data, note that the String of the local timestamp in the facts table is kept. In a large dataset this would bloat the table and probably not be necessary. Strictly speaking, the offset is also unnecessary as you should be able to recalculate what it was given the timestamp in UTC and the exact time zone of the event producing service. Practically speaking however, if you are going to need this information a lot for your analysis, you are simply trading off later compute time against storage.

Note that a lot of metadata about the store business day in the Store Hours table is also kept - this helps to ensure that not only the analytic calculations are correct, but that the generated data is correct (see "Test data validation" below). This is a surprisingly common issue where test data is produced - it looks good to the known edge cases, but doesn't end up correct to the unknown edge cases. It's in exactly these scenarios that you want to know more about how it was produced, so you can fix it.

Test data validation¶

In the Data Generator Notebook, you can also inspect the generated data to ensure that it conforms to the changes expected over the difficult time window of 1st April to 3rd April in the Chatham Islands.

Review the following output and consider what you've read so far about the changes over these few days, and then take a look at the timestamps and calculations to see how each plays out:

Day: 2023-04-01 opening time UTC: 2023-03-31T19:15:00+00:00 opening time local: 2023-04-01T09:00:00+13:45 timezone offset at store open: 49500 total hours elapsed during store business day: 25 total count of sales during business day: 625 and sales amount in cents: 31250 total hours elapsed during calendar day: 24 total count of sales during calendar day: 600 and sales amount in cents: 30000 closing time UTC: 2023-04-01T20:14:59+00:00 closing time local: 2023-04-02T08:59:59+12:45 timezone offset at store close: 45900 Day: 2023-04-02 opening time UTC: 2023-04-01T20:15:00+00:00 opening time local: 2023-04-02T09:00:00+12:45 timezone offset at store open: 45900 total hours elapsed during store business day: 24 total count of sales during business day: 600 and sales amount in cents: 30000 total hours elapsed during calendar day: 25 total count of sales during calendar day: 625 and sales amount in cents: 31250 closing time UTC: 2023-04-02T20:14:59+00:00 closing time local: 2023-04-03T08:59:59+12:45 timezone offset at store close: 45900 Day: 2023-04-03 opening time UTC: 2023-04-02T20:15:00+00:00 opening time local: 2023-04-03T09:00:00+12:45 timezone offset at store open: 45900 total hours elapsed during store business day: 24 total count of sales during business day: 600 and sales amount in cents: 30000 total hours elapsed during calendar day: 24 total count of sales during calendar day: 600 and sales amount in cents: 30000 closing time UTC: 2023-04-03T20:14:59+00:00 closing time local: 2023-04-04T08:59:59+12:45 timezone offset at store close: 45900

This test data generator has been through several iterations to capture the specifics of various scenarios that Tinybird customers have raised; hopefully you will also find it helpful.

Query correctly with time zones and DST¶

Now that you've have looked at the test data, let's work through understanding some examples of the correct way to query it, and where it can go wrong.

In the companion Workspace, this section is in the Pipe Aggregate_Querying.

Naively querying by UTC¶

If you naively query by UTC here, you get an answer that looks correct - sales start at 9am and stop at 5pm when London is on winter time, which matches UTC.

SELECT

store,

toStartOfFifteenMinutes(timestamp_utc) AS period_utc,

sum(sale_amount) AS sale_amount,

count() as sale_count

FROM sales_data_raw

where store = 'London' AND toDate(period_utc) = toDate('2023-03-24')

GROUP BY

store,

period_utc

ORDER BY period_utc ASC

| store | period_utc | sale_amount | sale_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| London | 2023-03-24 09:00:00 | 88418 | 7 |

| London | 2023-03-24 09:15:00 | 29159 | 3 |

| London | 2023-03-24 09:30:00 | 35509 | 3 |

The essential mistake here is blindly converting the UTC timestamp in period_utc to a date, however as the time zone aligns with UTC, it has no impact on these results.

Naively querying a split time zone¶

However if we naively query Auckland applying a calendar day to the UTC periods, we get two split blocks at the start and end of day.

This is because you're actually getting the end of the day you want, and the start of the next day, because of the ~+13 UTC offset.

select * from sales_15min_utc_mv

where store = 'Auckland' AND toDate(period_utc) = toDate('2023-03-24')

ORDER BY period_utc ASC

| store | period_utc | sale_amount | sale_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auckland | 2023-03-24 00:00:00 | 71538 | 6 |

| Auckland | 2023-03-24 00:15:00 | 51795 | 5 |

| Auckland | 2023-03-24 00:30:00 | 67106 | 7 |

The same mistake is made as above, with the blind conversion of the UTC timestamp to a date, however in this case it's more obvious that it's wrong as very few time zones map 0900 local exactly to midnight.

Try the same query again with the Tokyo store, and see how the mistake is easily hidden.

Aggregating by timestamp over a period¶

A convenience of modern time zone and DST definitions is that they can all be expressed in 15 minute increments (in fact, underlying Tinybird assumes this is true to drive processing efficiency), so if you aren't sure what aggregation period is best for you, start with 15mins and see how your data set grows, as you can query any larger period as groups of 15min periods.

To remind you again of the test data: You have a table containing sales data for a set of stores. Your data has columns for a store, a timestamp in UTC, and a sale_amount. In Tinybird, you can quickly and efficiently pre-calculate the 15min periods as a Materialized View with the following query:

SELECT

store,

toStartOfFifteenMinutes(timestamp_utc) AS period_utc,

sumSimpleState(sale_amount) AS sale_amount,

countState() AS sale_count

FROM sales_data_raw

GROUP BY

store,

period_utc

ORDER BY period_utc ASC

Using this, you can then produce any larger period for a given window of that period. See the next example for how to break it into local days.

Querying by day and time zone¶

In the example Workspace, see the sales_15min_utc_mv Materialized View.

Building on the previous example, this query produces a correct aggregate by the local time zone day for a given store, timezone, start_day and end_day (inclusive). We also feature use of Tinybird parameters, such as you would use in an API Endpoint.

Note that you're querying the tricky Chatham store here, and over the days with the DST change, so you can see the pattern of transactions emerge.

This example uses Tinybird parameters for the likely user-submitted values of timezone, start_day and end_day, and you are selecting the data from the sales_15min_utc_mv Materialized View described above.

%

Select

store,

toDate(toTimezone(period_utc, {{String(timezone, 'Pacific/Chatham')}})) as period_local,

sum(sale_amount) as sale_amount,

countMerge(sale_count) as sale_count

from sales_15min_utc_mv

where

store = {{String(store, 'Chatham')}}

and period_local >= toDate({{String(start_day, '20230331')}})

and period_local <= toDate({{String(end_day, '20230403')}})

group by store, period_local

order by period_local asc

| store | period_local | sale_amount | sale_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chatham | 2023-03-31 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-01 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-02 | 31250 | 625 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-03 | 30000 | 600 |

Note that the DateTime has been converted to the target time zone before reducing to the local calendar day using toDate, and that the user input is converted to the same Date type for comparison, and the column has been renamed to reflect this change.

Also note that the time zone parameter is a String, which is required by Tinybird. It's up to you to ensure you supply the right time zone string and Store filters here.

Because the Data Source in this case is a Materialized View, you should also be careful to use the correct CountMerge function to get the final results of the incremental field.

Validating the results¶

You can validate the results by comparing them to the same query over the raw data, and see that the results are identical.

select

store,

toDate(substring(timestamp_local, 1, 10)) as period_local,

sum(sale_amount) as sale_amount,

count() as sale_count

from sales_data_raw

where

store = 'Chatham'

and toDate(substring(timestamp_local, 1, 10)) >= toDate('20230331')

and toDate(substring(timestamp_local, 1, 10)) <= toDate('20230403')

group by store, period_local

order by period_local asc

| store | period_local | sale_amount | sale_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chatham | 2023-03-31 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-01 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-02 | 31250 | 625 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-03 | 30000 | 600 |

Querying with a lookup table¶

In our test data, the store day doesn't match the local calendar day - if you recall it was specified that it starts at 0900 local time. Fortunately, we can use a lookup table to map the store day to our UTC timestamps, and then use that to query the data. This is often a good idea if you have a lot of data, as it can be more efficient than using a function to calculate the mapping each time.

select

store,

store_date,

sum(sale_amount),

countMerge(sale_count) as sale_count

from sales_15min_utc_mv

join store_hours_raw using store

where period_utc >= store_hours_raw.store_open_time_utc

and period_utc < store_hours_raw.store_close_time_utc

and store_date >= toDate('2023-03-31') and store_date <= toDate('2023-04-03')

and store = 'Chatham'

group by store, store_date

order by store_date asc

| store | period_local | sale_amount | sale_count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chatham | 2023-03-31 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-01 | 31250 | 625 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-02 | 30000 | 600 |

| Chatham | 2023-04-03 | 30000 | 600 |

Note that the extra hour of business moves to the 1st of April, as that store day doesn't close until 0859 on the 2nd of April, which is after the DST change.

Use Materialized Views to pre-calculate the data¶

Several of these examples have pointed to a Materialized View, which is a pre-calculated table that is updated incrementally as new data arrives.

These are also prepared for you in the companion Workspace, specifically for the UTC 15min rollup, and the normalized 15min rollup.

Next steps¶

- Read Tinybird's "10 Commandments for Working With Time" blog post to understand best practices and top tips for working with time.

- Understand Materialized Views.

- Learn how to dynamically aggregate time series data by different time intervals (rollups).

- Got a tricky use case that you want help with? Connect with us in the Tinybird Slack community.